Unmourned, the Barnes & Noble bookstore on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Eighth Street closed its doors for good at the end of 2012. It was only the latest of several independent bookstores in The Village that have shut its doors in recent years including the Eighth Street Bookstore, a mecca for booklovers for years, whose demise was by contrast a cause for mourning. (A friend of mine spotted Allan Ginsburg browsing there one day and went over to greet him. “Do I know you?” the poet asked. My friend said no, he was just an admirer. “Oh, that’s a relief,” Ginsburg said, “For a moment there I thought you’d been a lover.”) But the corner B&N was a fixture for decades (previously it had been a Dalton’s Bookstore) and its disappearance leaves a void like the loss of someone who was never a close friend but who you’d gotten used to seeing around the neighborhood. Back in the Nineties, of course, B&N was an apparently unstoppable behemoth, planting big box stores in every part of town, driving independent bookstores to extinction. But that was a different time when Tower Records still dominated the CD business (when there was a CD business to dominate.) But all the while that B&N and Borders, its principal rival, were duking it out for customers the retail book business was migrating online. So the bankruptcy of Borders a few years ago was less like a victory for B&N than a harbinger of things to come. Although B&N has established its own online book site it is no match for the new behemoth on the block, amazon.

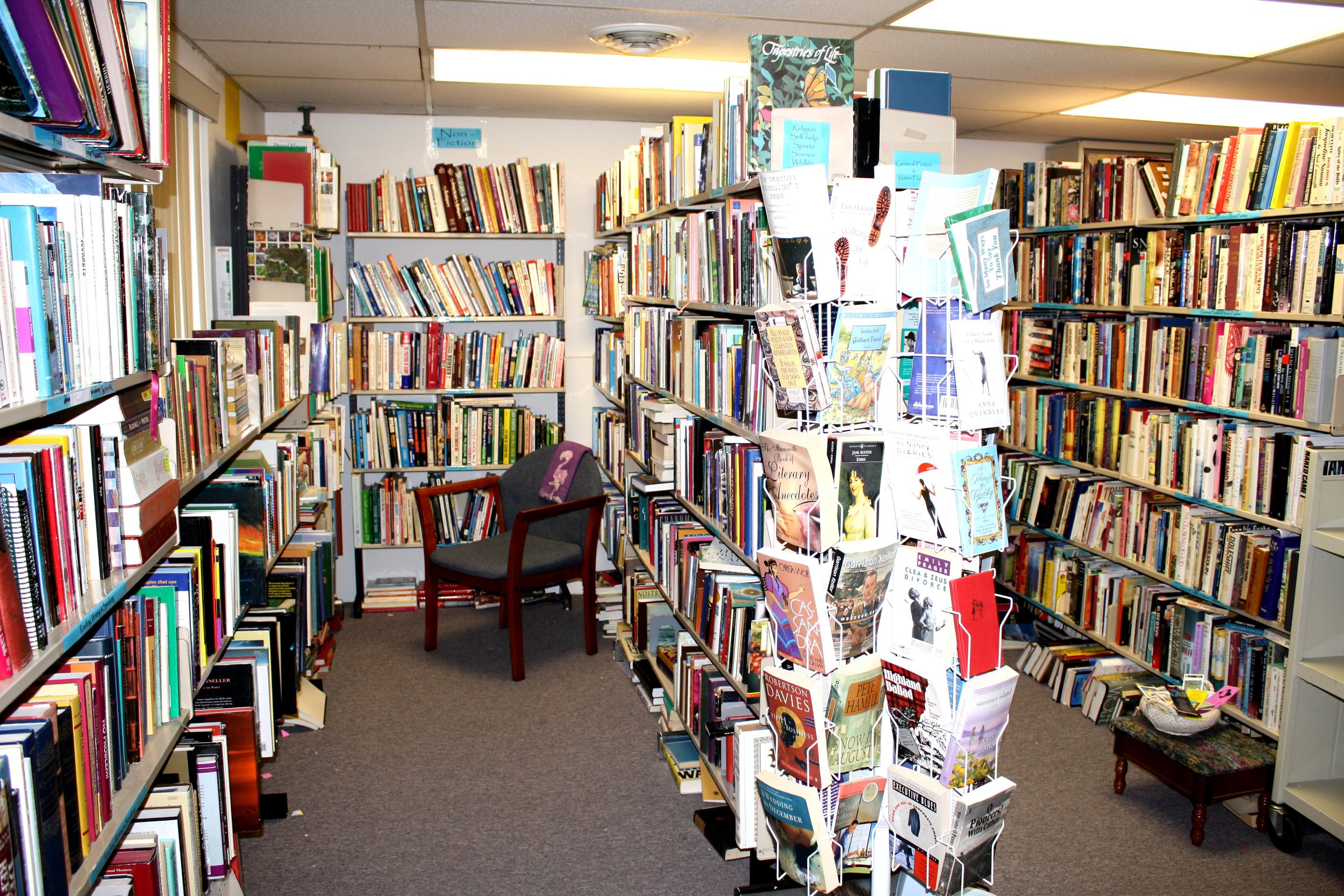

In a desperate (but to my mind misguided) effort to woo customers to shop in its brick and mortar stores B&N began to strip books – books! – from its shelves, replacing them with Moleskine notebooks, reading lights, greeting cards and all manner of gewgaws. To save money, several B&N superstores were shuttered, leaving even prime locations without any bookstore. Ebook sales soared and ebook readers flew off the shelves. But then something strange happened. Ebook sales, while certainly robust, began to plateau. Sales of ebook readers flagged as customers opted in increasing numbers for tablets, which in addition to allowing them to store and read ebooks to their heart’s content, also provided them with a profusion of nonliterary distractions – email, videos, Facebook and Angry Birds. And, perhaps most astonishingly, independent booksellers, virtually written off (puns intended), began to make a comeback. It’s a decidedly modest comeback to be sure, but Publisher’s Weekly, the industry’s trade journal, reports that over sixty independent bookstores opened for business in the U.S. last year. Clearly they’re satisfying a demand that can’t be entirely satisfied online. Understandably, publishers have a problem selling digital books (leave aside the pricing controversy that has landed Apple in court and forced several publishers to settle with the Justice Department): a book displayed in a bookstore is not only selling itself but older titles by the same author (known as a backlist) as well, the idea being that if you’re going to buy one book by John Grisham or Nora Roberts you may be tempted to buy an earlier novel by Grisham or Roberts if the author’s other books are within easy reach. Customers are far more disposed to select just a single book by an author online than go searching through the author’s backlist – and backlist sales are among publishers’ most reliable sources of revenue. (It’s basically found money; most of the initial upfront costs – author advances, editing, printing, promotion and distribution – have already been covered.) But independent bookstores are a different species than B&N and other big retailers. You can feel it immediately when you step into one. Independent bookstores, aside from usually being smaller, tend to be more intimate. (I am thinking in particular of Three Lives, St. Mark’s Bookstore and Shakespeare’s, three cherished independents in The Village that managed to outlast the B&N superstores that once threatened to put them out of business.) Just like in a gallery or museum, you can sense the curatorial influence; each title seems to have been personally selected and the people who work in these stores tend to know about the books they’re selling and over time they begin to know their customers’ tastes as well. That means that a customer can walk into a store and say, “I’m going on vacation and I need a novel to read, what do you suggest?” and walk out with a book that will delight him or her. That kind of passion for books was what was -- and is -- missing from Barnes & Noble (and I say this as someone whose books whose sales the retailer has helped promote). And passion is one thing that you will never find online, either.